ADHD Prescribing

Around three or four decades ago, it became fashionable in psychiatry to classify mental disorders into distinct diagnostic categories. The rationale was that it would move people away from circular arguments about aetiology, and towards practical and reliable disease definitions that would be useful for clinicians and academics. This led to a huge number of new disease labels, one of which was ADHD.

Of course, inattentive, impulsive, and hyperactive children have always existed, and it’s difficult to quantify the exact effect of labelling children with a disease name, rather than approaching them ‘the old-fashioned way’, whatever that might be.

As every GP knows, the diagnosis of diseases like ADHD is far from straightforward. They prompt us to do the difficult job of drawing lines between the normal and the abnormal, when those lines are often grey and blurred. With ADHD, it’s further complicated by the media and celebrity discourse about the disease. Hillary Clinton, for example, has suggested that the medical profession are too quick to diagnose children whose problems are simply normal characteristics of childhood.

It’s not just celebrities and politicians though. The concerns about overmedicalisation have also been raised from within the medical profession. Shifting definitions and commercial influences have been suggested as important drivers, and it has been noted that elevated medication costs, adverse events, and psychological harms are all potential consequences.

So where does that leave us, as frontline GPs?

In a recently published systematic review that I contributed to, studies that investigated medication taking in ADHD patients and their carers were synthesised. It highlighted a complex array of factors that contribute to decisions about whether to take medications, including acceptance of the diagnostic label, anticipated and actual side effects of medications, and the external influences of school, friends, and the media. An important theme was the concept of ‘trade-offs’, as families described having to weigh up the numerous positive and negative consequences of medications on various aspects of their lives.

The 2018 NICE guideline on ADHD reaffirms that diagnosis and initiation of treatment should be done in secondary care. However, as trusted family doctors and patient advocates, we will clearly be called on for advice and support. Indeed, the new guideline is much more explicit than previous versions in outlining strategies for sharing decisions relating to ADHD management: there is more focus on involving families, more specific recommendations on conversations around medication adherence, as well as proactive encouragement to discuss patient preferences around discontinuing or changing medication.

Although our role in ADHD is primarily to support secondary care colleagues, we are well placed to help families make sense of diagnostic and treatment uncertainties, and support them to make decisions that work for them.

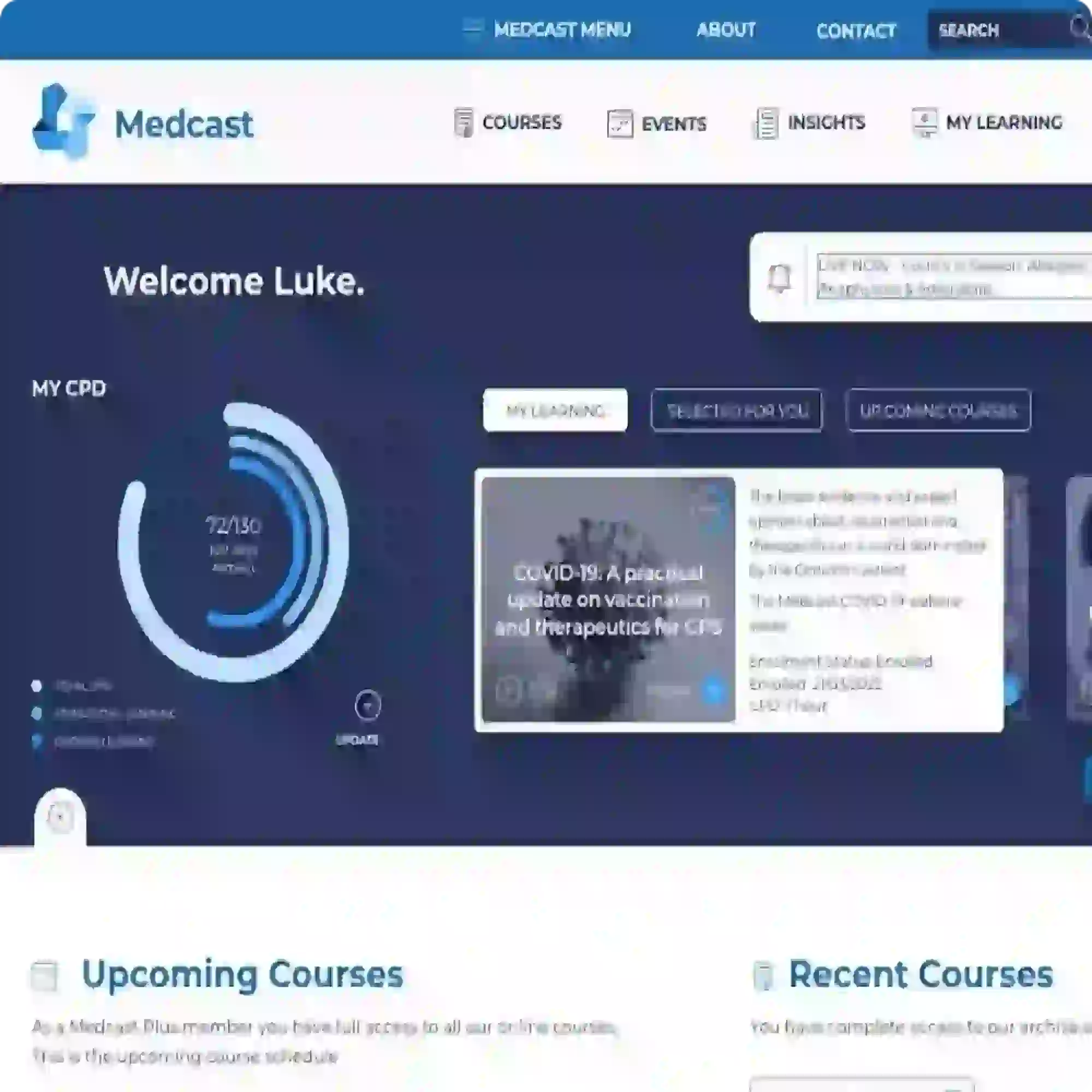

Hot Topics Courses

Our 2019 national tour of one-day Hot Topics courses commences 23 February through to 30 March. Click here for the details.

Can't make it on the day? Watch the 2018 Hot Topics in high-definition or sign-up to our Hot Topics 2019 LIVE webinar series.

This blog was originally published via the NB Medical Hot Topics Blog, in March 2019.

Ahmed is an NHS GP in Hertfordshire, a Senior Clinical Teaching Fellow at UCL Medical School and a Hot Topics presenter. He has a monthly research column in the British Journal of General Practice.

Become a member and get unlimited access to 100s of hours of premium education.

Learn moreAnthony is a retired engineer, who is compliant with his COPD and diabetes management but has been struggling with frequent exacerbations of his COPD.

Whilst no longer considered a public health emergency, the significant, long-term impacts of Covid-19 continue to be felt with children’s mental health arguably one of the great impacts of the pandemic.

Your next patient is Frankie, a 5 year old girl, who is brought in by her mother Nora. Frankie has been unwell for the past 48 hours with fever, sore throat and headache. The previous day Nora noticed a rash over Frankie’s neck and chest which has since spread over the rest of her body.