Men are from Mars… or are they?

Men and women are different from each other. What a profound statement that is! Also one that could get me into a lot of trouble, particularly if it led to a discussion about whether that difference was genetically or culturally determined. I’m going to say it anyway, because I’m thinking about depression and suicide and the ways in which men and women express their distress differently.

For a very long time medical research was only done on male subjects. It was assumed that what was true for men would also be true for women. It wasn’t until late in the 20th century that researchers came to realise that, physiologically, men and women are actually different from each other. They metabolise drugs differently, they have different responses to changes in exercise and diet and they even have different blood chemistry while they sleep.

In mental health we know that more men die by suicide but that more women report depressive symptoms. As others have before me, I can’t help but wonder whether we are asking men the right questions?

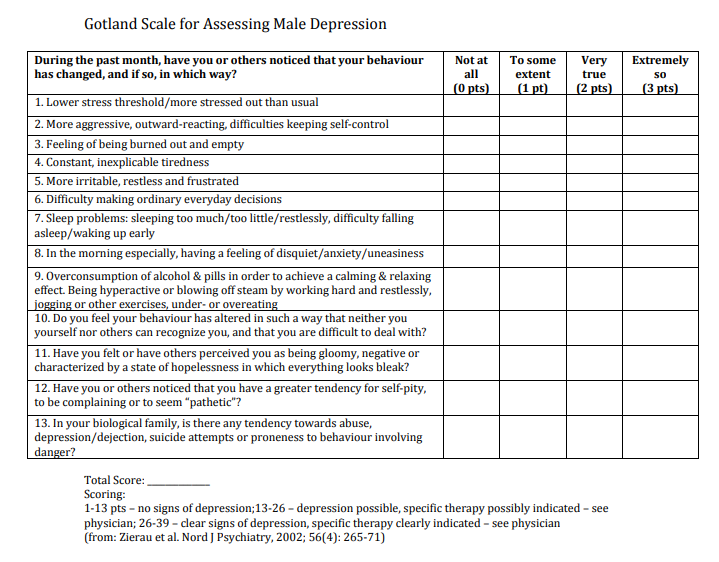

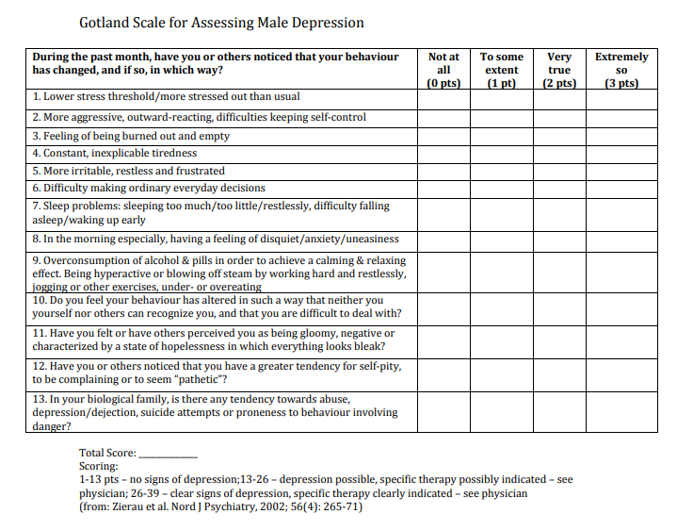

The Gotland Scale for Assessing Male Depression (1)

In the 1980s a study done in Sweden suggested that routine screening tools for depression seemed not to be detecting depression in men as well as they were in women. Out of that study emerged the Gotland Male Depression Scale. There is no suggestion that that “male depression” is a different entity to “female depression” but that men express their experience of depression differently so will respond to different lines of enquiry. The Gotland scale was developed on the basis of the proposition that men were less likely to report low mood and more likely to report irritability, restlessness, frustration, anger, stress and reliance on substances. Here’s what it looks like:

Is it just about sex?

I suspect that this difference is not just gender related but that there’s also something that reflects personality style. Those with more irritable personalities, irrespective of gender, may well become more irritable when depressed leaving the door open for us to misinterpret their symptoms and miss a depression diagnosis irrespective of their sex. Maybe they aren’t pushy, demanding, critical, irritable and complaining after all – maybe they are depressed!

The bottom line

We need to be careful about our use of psychological instruments, and we also need to be aware that many of the questions we (and the instruments) traditionally ask people about their mental and emotional health are skewed towards women’s mental health symptoms and issues and have little resonance for men.

Links

Have you ever been on your way to work and asked yourself “I don’t really feel well . . . should I really be working clinically today” – and yet still turned up and completed a full day’s work?

*In April 2021, approximately 619,000 older Australians (aged 65 and over) were employed in the labour force", and at 66 years, I’m proud to be included in this statistic. By Tessa Moriarty

For as long as I have been in practice (and that’s a long time!) I have done my best to avoid looking after old people.